This is an instructional manual for teaching the extended Wylie transliteration system to speakers of Tibetan languages. The manual is based on the Tibetan and Himalayan Digital Library extended Wylie system as described in Nathaniel Garson and David Germano’s “Extended Wylie Transliteration Scheme” (January 31, 2003 update).

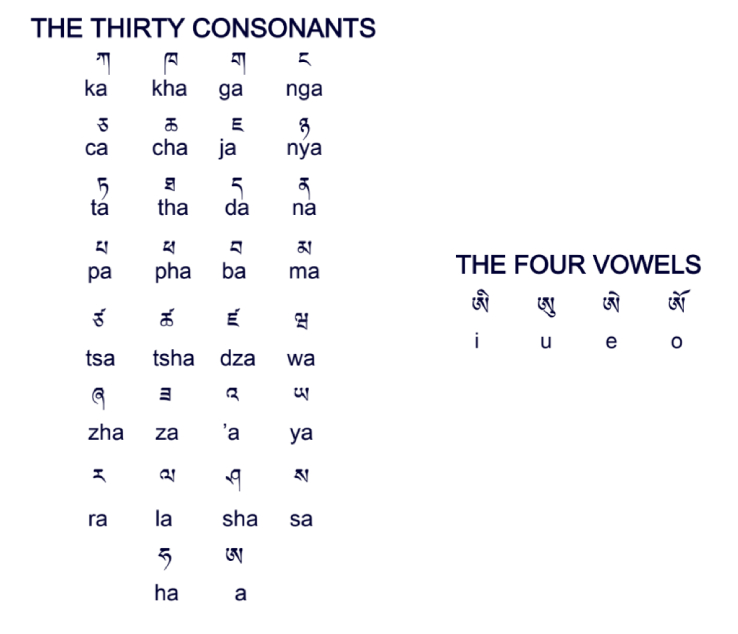

This unit groups the Tibetan alphabet in several sections according to a hierarchical order of complexity. The standard for complexity rests on the number of letters required to render a Tibetan character (e.g., the ca, cha, tsha progression) as well as deviations from the norm (e.g., nga, zha, and ‘a).

Two-letter combinations are the simplest transliteration units and are introduced first. Three-letter aspirate combinations introduce a new element that is predictably transliterated. These should be taught as a group and randomly contrasted to their non-aspirate counterparts (e.g., ca and cha, ta and tha).

Three-letter non-aspirate combinations require some extra attention as the basis for their transliteration has not proved entirely intuitive, particularly in the case of nga, nya, and dza. Tsha issometimes confused for either cha or tsa in transliteration and should be presented in contradistinction to these. Introducing the vowels remains last, although this could also be carried out with the support of a consonant (e.g., ra, re, ri, ro, ru) and followed by the individual vowels. The a chung is a constant source of confusion. Its transliteration should be clearly explained at every stage of instruction.

TWO-LETTER COMBINATIONS

ཀ ག ཅ ཇ ཏ ད ན པ བ

ka ga ca ja ta da na pa ba

མ ཝ ཟ ཡ ར ལ ས ཧ

ma wa za ya ra la sa ha

THREE-LETTER COMBINATIONS

Aspirates

ཁ ཆ ཐ ཕ

kha cha tha pha

Non-aspirates

ང ཉ ཙ ཛ ཞ ཤ

nga nya tsa dza zha sha

FOUR-LETTER COMBINATION

ཚ

tsha

VOWELS AND A CHUNG

ཨ ཨི ཨུ ཨེ ཨོ འ

a i u e o ‘a

COMBINATION and REVIEW The introduction of the vowels and consonants proceeds swiftly and offers the first opportunity for review. During review, the instructor presents an existing word in script, which the student then transcribes. Wylie transcription-to-script exercises should be emphasized if the student requires reading fluency in Wylie. Words that exhibit random characteristics are to be given successively. Mistakes should be noted and the respective exercises repeated at intervals. Students occasionally make consistent errors with a particular transliteration. These should be followed up in further stages of instruction until the concept is thoroughly understood. The transliteration of the tsheg can be introduced here or in the next unit. Teaching the entire set of combinations outlined in this guide takes between one and two hours.

Examples:

ལོ་ བུ་ རེ་བ་ མི་ ཚོ་ དུ་ རི་ ཇོ་བོ་ དེ་ སུ་ འོ་

lo bu re ba mi tsho du ri jo bo de su ‘o

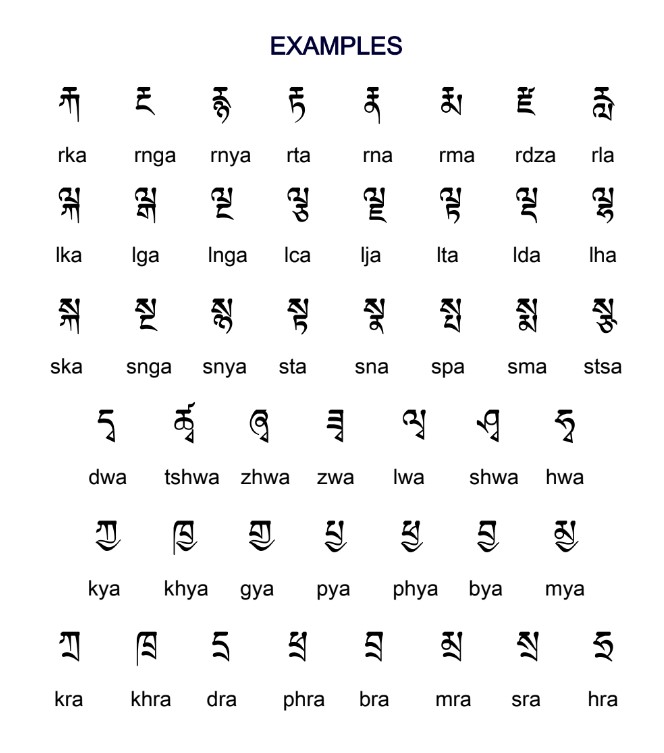

SUPERSCRIBED AND SUBSCRIBED COMBINATIONS

Superscribed (ra mgo, la mgo, and sa mgo) or subscribed (ya rtags, ra rtags, la rtags, and wa rtags) combinations can be introduced first and then combined, with or without vowels. Progressions such as spa, spya, spyi and rka, rkya, rkyo are useful drills. Students often need assistance with the transliteration of vowels, which becomes noticeable at this stage. skyao written instead of skyo or sbua written instead of sbu are common mistakes. Errors in transliterating syllables without vowels can arise right after teaching the vowels (e.g., sk for sku and smr for smra). I found it helpful telling students to place the vowel after the root letter if there is one or an ‘a’ if there is not.

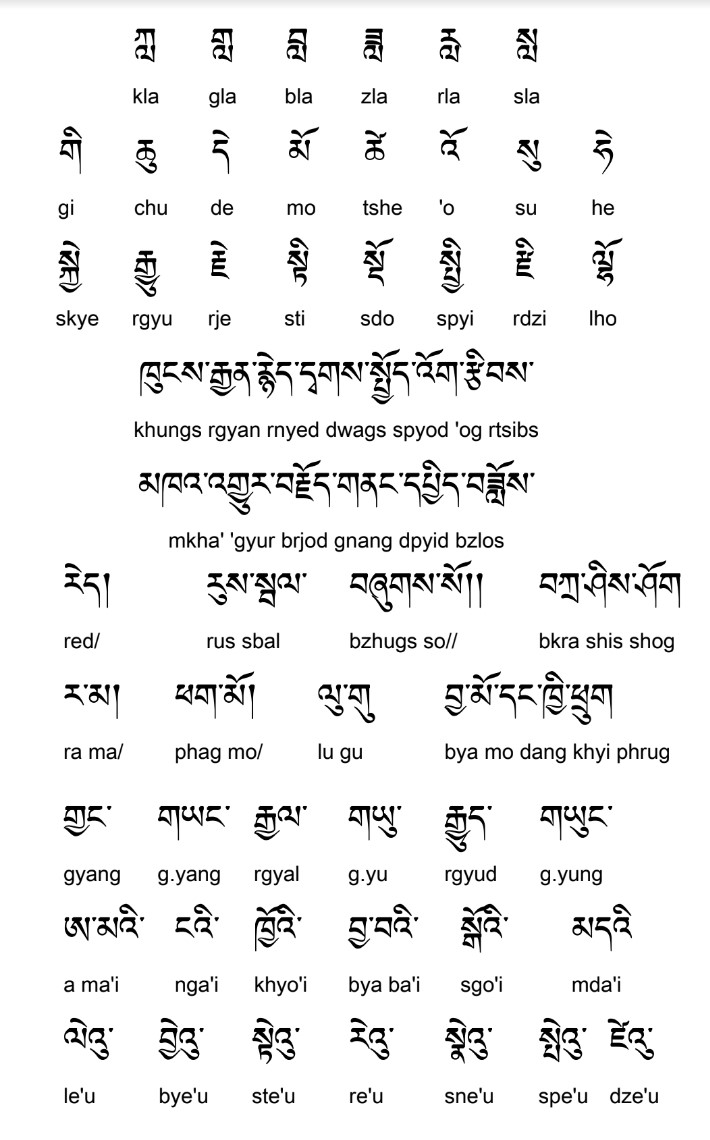

PREFIXES, SUFFIXES, AND THE POST-SUFFIX

Either the prefix or suffix can be taught next. Examples should first introduce a particular prefix (mgo, mdze, mdo), and then randomly present them in random fashion (‘di, mkho, gtso bo). The suffix is introduced in the same way; nan tan, sman, sngon, and gzhung, bcad, gtor. It is not necessary to emphasize every single suffix, but it is important to spend extra time on the a chung as prefix, root letter, and suffix (‘og, ‘das, mkha’, ‘ba’, ‘os, mnga’, etcetera).

Occasionally, mistakes such as sogram or sgoram for sgrom, occur. Horizontal and vertical reading priorities should be explained to reinforce the order of transliteration. If students ask why a syllable such as bsil is not rendered basila, it is important to remind them that vowels are only associated with the root letter cluster. The post-suffix sa is intuitively grasped when taught in this sequence. It is also important to create gradual progressions of exercises that explore various letter groups and culminate in a complex cluster such as bsgrubs or brgyangs. When done carefully enough, such exercises will expose areas where the student needs more practice. I have found it useful and practical to draw out vocabulary for students out of randomly chosen Tibetan script books during instruction, but pre-prepared exercises are also an option.

Examples:

གྱ་ གྱང་ རྒྱང་ བརྒྱང་ བརྒྱངས་

gya gyang rgyang brgyang brgyangs

ངུ་ མགུ་ ངུབ་ རྔུབ་ བརྔུབ་ བརྔུབས་

ngu mgu ngub rngub brngub brngubs

THE SHAD

At some point, either after teaching the transliteration of complex syllables or during, the usage of the shad (i.e. / ) after words should be demonstrated. The tsheg can be reviewed here if necessary.

Tibetan writing will generally omit the shad when preceded by a ga (and occasionally ka and sha) syllable ending at the end of a ‘clause’ or ‘sentence’ usually terminated by a shad. In these cases, the transliteration of the shad will follow the written text character for character, mimicking possible inconsistencies and peculiarities found in the text. The transliteration must therefore preserve the original text and not introduce a shad where one might be tempted to place one.

Examples:

རྟ། ནོར། ལུག་གསུམ།

rta/ nor/ lug gsum/

རི་མགོ་ན་ཉལ་ན་དཀའ།

ri mgo na nyal na dka’/

གཅིག

gcig

USAGE OF G.YA AND GYA

The special use of the period (.) to indicate a ga prefixed to a ya root letter as opposed to a ga root letter with a ya subscript is unusual enough that it should be introduced separately. It is not a hard concept to understand, but it is easy to forget. It is an exception to other Wylie rules, with good reason. Repeated exercises at intervals are recommended.

Examples:

གཡུ་ གཡོ་ གཡུལ་ གཡང་ གཡེང གཡག་ གཡའ་ གཡུང་ གཡེལད་

g.yu g.yo g.yul g.yang g.yeng g.yag g.ya’ g.yung g.yeld

A CHUNG IN GENITIVE CONSTRUCTIONS AND OTHER CONNECTED SYLLABLES

The a chung holds vast potential for confusion due to the non-letter character used to render it in transliteration. Much of the confusion can be avoided if the student can regard the ‘a as if it were a standard consonant, like na or ra. The a chung also presents ambiguities in that it helps form syllables that fuse to the end of other syllables (e.g., nga’i, re’u, bla ma’ang). At a quick glance the a chung encourages ambiguity in seemingly introducing a second root letter in the slot reserved for the suffix, as well as a second vowel. This apparent jumble is easy to transliterate unambiguously if the student can regard the cluster as two distinct syllables without the tsheg between them (e.g., bye’u as bye and ‘u without the intervening tsheg).

NUMERALS

Teaching the transliteration of numerals (0-9) is straightforward.

Example:

ངའི་སྐྱེས་ལོ་༡༩༦༨རེད། is transliterated as nga’i skyes lo1965red/. If in the text there is a space between the number and the syllables that precede and follow it, an underscore (_) is used to represent the white space. Thus,

ངའི་སྐྱེས་ལོ་ ༡༩༦༨ རེད།

is transliterated as nga’i skyes lo_1965_red/.

For dates, the standard convention is a tsheg before a number but no tsheg after a number. Thus, a statement at the end of a book’s introduction indicating that the introduction was written on November 11, 2000 is སྤྱི་ལོ་༢༠༠༠ཟླ་༡༡ཚེས་༡༩ལ།

and it is transliterated as spyi lo 2000zla 11tshes 19la/. If there are spaces in the text itself around the numbers so that it looks like this,

སྤྱི་ལོ་ ༢༠༠༠ ཟླ་ ༡༡ ཚེས་ ༡༩ ལ། it is transliterated spyi lo _2000_zla _11_tshes _19_la/.

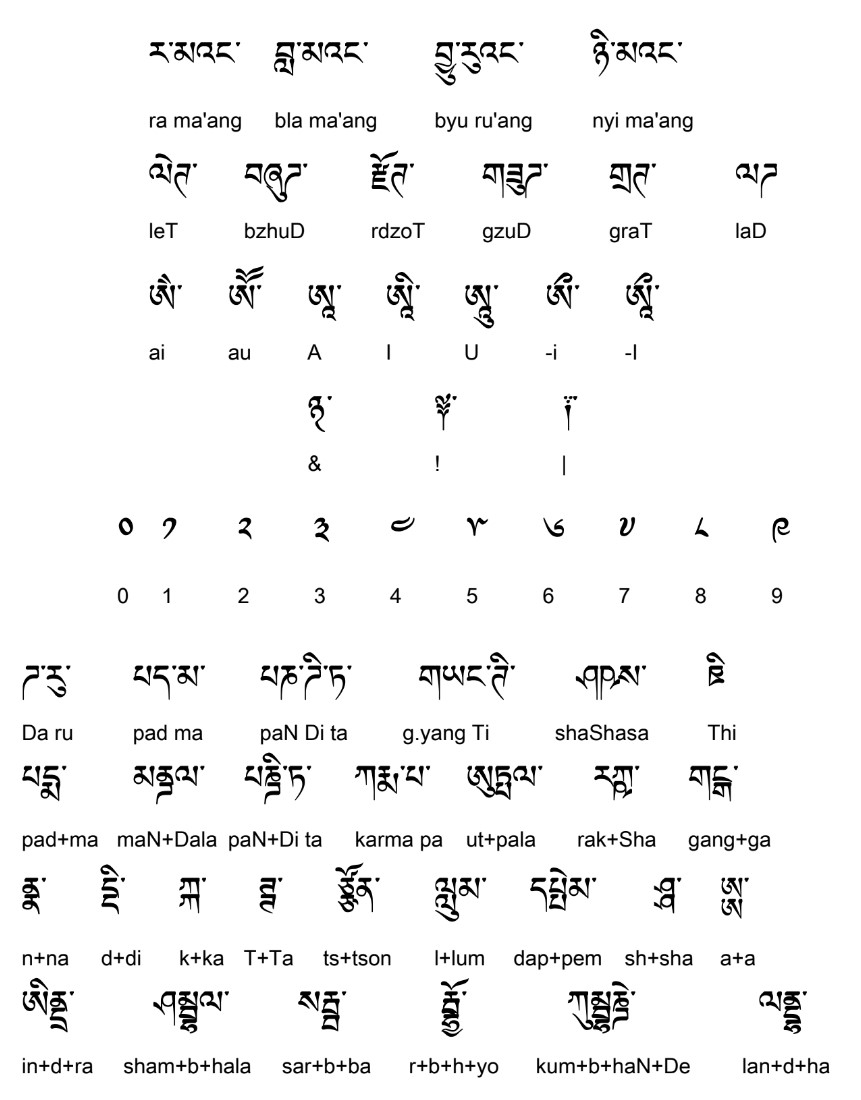

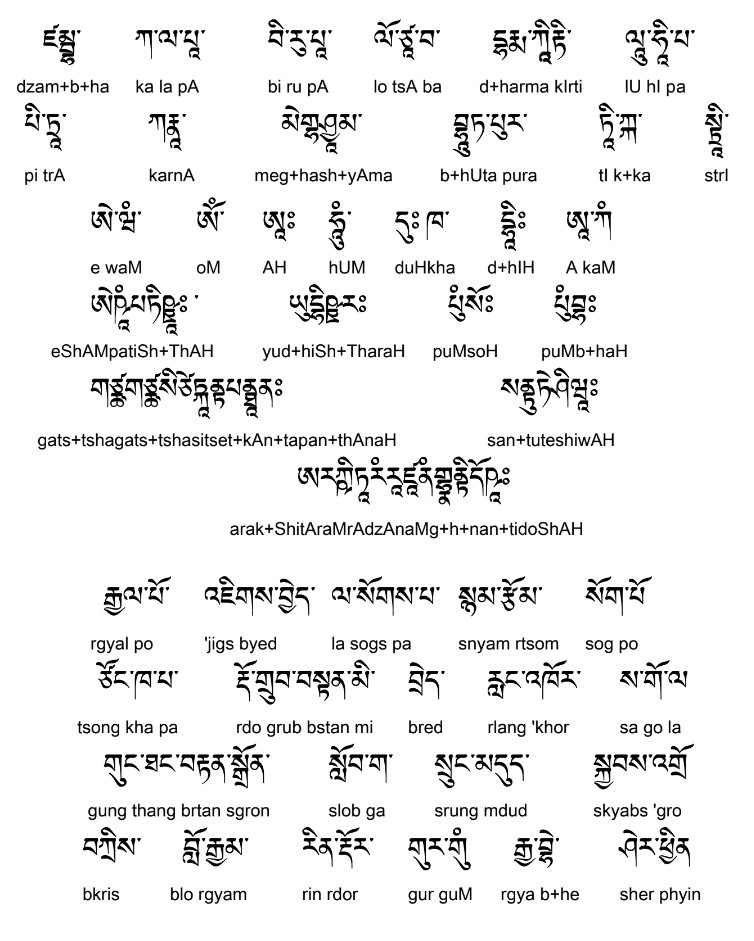

SANSKRIT

Long Vowels

Long vowels, indicative of Sanskrit works or other foreign influences, are transliterated using the capitals of the respective vowels. Long vowels are indicated in Tibetan by the presence of a small a chung below the root letter stack, yet another opportunity for confusion. The a chung in such cases does nothing else but show a very specific characteristic of the vowel. It runs contradictory to a number of rules, in that an element at the bottom of a letter stack interacts with an element at the top of the stack regardless of what is between them, and one capital letter is used to transliterate two Tibetan characters. This contradiction is partly warranted by being faithful to the Sanskrit vowels, which use one sign to indicate a sound. However, although there is no long ‘e’ or ‘o’ character in Sanskrit, these combinations continue to be useful in rendering a variety of Tibetan loan words, particularly names. The usage of capital letters in transliteration is ineffective if capitals are also used for other purposes, such as at the beginning of the sentence or to render names. Such stylistic preferences compromise transliteration accuracy. If both are necessary, the instructor will need to negotiate ad hoc usage rules.

Retroflex Letters and Non-Standard Stacks

The six retroflex letters used primarily for words of Sanskrit origin (e.g., paN+Dita, tiSh+Tha) should also be practiced in conjunction with long vowels, even if the examples are made up for the sake of the exercise (e.g., DI, ShU, NO). It should also be pointed out that for the three-lettered retroflex letters Sha and Tha, only the first letter of the transliteration needs to be capitalized.

Consonant stacks that do not follow Tibetan grammar rules are non-standard and are indicated by a plus sign (e.g., pad+ma, lan+d+ha). It is important to point out that Sanskrit stacks often embed two or more syllables that must be skillfully extracted (e.g., rak+Sha, ut+pala). At this point, there is some potential for the student to start using the plus sign to transliterate even standard Tibetan stacks,especially when Tibetan grammar rules allow Sanskrit stacks to take on an indigenous appearance (e.g., karma pa). The special use of the plus sign will then need to be reiterated.

It is sometimes the case that Tibetan language speakers are not familiar with the pronunciation of an original Sanskrit word or stack. In these cases, explaining the pronunciation of the original Sanskrit often shows how transliteration of Sanskrit loan words really just follows the rules of transliteration the student has already learned.

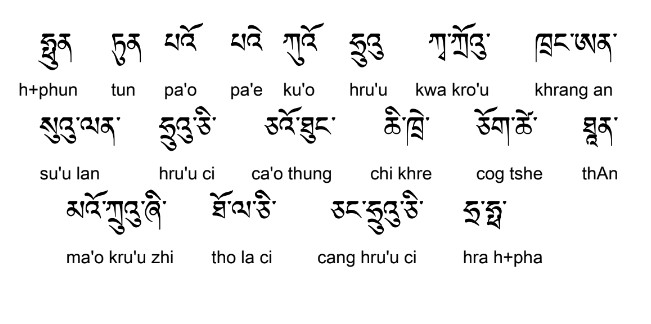

WORDS OF CHINESE ORIGIN

Chinese loan words and names make frequent use of the a chung joined with a vowel in place of a suffix (e.g., su’u lan, ku’o) as well as long vowels (e.g., thAn). The a chung and long vowels should be reviewed within the context of Chinese loan words, if relevant. Chinese loanwords make some use of the non-standard stack, h+pha, to indicate the ‘f’ sound (e.g., hra h+pha), for which there is no written convention in Tibetan. The use of the + sign should likewise be reviewed.

MISSPELLINGS AND NON-STANDARD TIBETAN

It is essential to communicate to students of the Wylie system that transliteration is an unambiguous, mechanical conversion from one set of symbols to another. Integrity during transliteration relies on faithful conversion of spelling mistakes (e.g., ‘jig byed, rlang ‘khor), intentional or unintentional non-standard clusters and contractions (e.g., bred, bkris), colloquialisms (e.g., rgya b+he), and orthography (e.g., ‘gog/, zha/). Correcting while transliterating is part of an editing process, which is a distinct priority separate from transliteration itself. Explaining this difference early on before a project will benefit the integrity of the transliterated text.

Example

rka རྐ rnga རྔ rnya རྙ rta རྟ rna རྣ རྨ རྫ རླ

ལྐ ལྒ ལྔ ལྕ ལྗ ལྟ ལྡ ལྷ

སྐ སྔ སྙ སྟ སྣ སྤ སྨ སྩ

དྭ ཚྭ ཞྭ ཟྭ ལྭ ཤྭ ཧྭ

ཀྱ ཁྱ གྱ པྱ ཕྱ བྱ མྱ

ཀྲ ཁྲ དྲ ཕྲ བྲ མྲ སྲ ཧྲ

ཀླ གླ བླ ཟླ རླ སླ

གི ཆུ དེ མོ ཚེ འོ སུ ཧེ

སྐྱེ རྒྱུ རྗེ སྟི སྤྱི རྫི ལྷོ

ཁུངས་རྒྱན་རྙེད་དྭགས་སྤྱོད་འོག་རྩིབས།

མཁའ་འགྱུར་བརྗོད་གནང་དཔྱིད་བཟློས།

རེད། རུས་སྦལ་ བཞུགས་སོ།། བཀྲ་ཤིས་ཤོག ར་མ། ཕག་མོ། ལུ་གུ བྱ་མོ་དང་ཁྱི་ཕྲུག

གྱང་ གཡང་ རྒྱལ་ གཡུ་ རྒྱུད་ གཡུང་ ཨ་མའི་ ངའི་ ཁྱོའི་ བྱ་བའི་ སྒོའི་ མདིའི་

ལེའུ་ བྱེའུ་ སྟེའུ་ རེའུ་ སྣེའུ་ སྤེའུ་ ཛེའུ་ ར་མའང་ བླ་མའང་ བྱུ་རུའང་ ཉི་མའང་

ལེཊ་ བཞུཊ་ རྫོཊ་ གཟུཊ་ གྲཊ་ ལཊ་ ཨཻ་ ཨཽ་ ཨཱ་ ཨཱི་ ཨཱུ་ ཨྀ་ ཨཱྀ་

༈ ༑